I love a good rant… especially one that begins with a strayed stream of consciousness about politics’ plight. As Mark Thomas Gibson took the stage at Cleveland Institute of Art’s Peter B. Lewis Theatre, a small request to drop the lights accompanied the passionate start. The dimmed atmosphere seemed to settle him. It settled me too. I attended out of curiosity, intrigued to learn more about the CIA’s current Curlee Raven Holton Inclusion Scholar. But within minutes, I realized I had found a new artist to follow (and did @darthgibson). Once the tributary of his opening remarks picked up, Gibson steered the lecture away from the shore into deeper waters. He immersed us in his artistic journey, tapping into the deep thoughts and processes of his artist lens that has lended to his success. Gibson’s intense interest in history frames much of his work, and at a time when I… maybe we… would rather avoid the politics altogether, he took the topic drawing utensils on. And wasn’t shy about it. His social critique was sharp, and it was clear that he was unafraid to go there…challenging narratives, confronting history, and presenting a vision of a world, forcing his audience to think, question, and reckon with all the things… both past and present.

Gibson’s presentation offered a glimpse into his mind and shared a series of works from his career that have served as historical memories, thoughts on paper, emotions evolved and lessons to be leveraged. Though his critiques felt deeply connected to current events, he exhibited a foundational fondness and critical curiosity of what has been with an interest of what can be beyond. Referencing Susie Wiles in his first slide, I knew I had made the right decision to attend, and though a bit of a rollercoaster, I was happy to ride.

He talked about his arrival at this place. A place of creation and care. A place inspired by dealing with epochs, which required further steps and reflections on the leadership of the nation and the leaders that were there and are there when these events happen, and furthermore questions why we don’t just do the Christian thing… time after time. The evening program was titled just that, Time After Time, and provided a packed hour of insights on what he thinks about often and how it manifests its influence into his work as an artist, professor, author, curator and all-around scholar. Just down the hall, the accompanying exhibition, Possibility For Repair, extended these ideas in the physical space of CIA’s Reinberger Gallery featuring his work alongside other local artists.

Within the first 15 minutes of the presentation, Gibson had already referenced a handful of books (Burn Out by Hannah Proctor / Going There by Richard J. Powell / Nero-politics by Achille Mbember / Scorched Earth by Jonathan Crary) that shape his work and how the lessons from them continue to be foundational factors for his practice. Continuing to set the context, he explained a talk by Art Spiegleman, from which sparked inspiration, focused on the “controversy” of Phillip Guston’s Now exhibition. What the hearsay was, what the truth was and how it all played out. Using this as a springboard to discuss why art is so important, he insinuated that there is immense power in art, and this is why some artists are attacked. But it is also why artists are important. Calling out the relevance of the students in the room, Gibson made it clear, he was not just there for himself, but for the next generation of creatives.

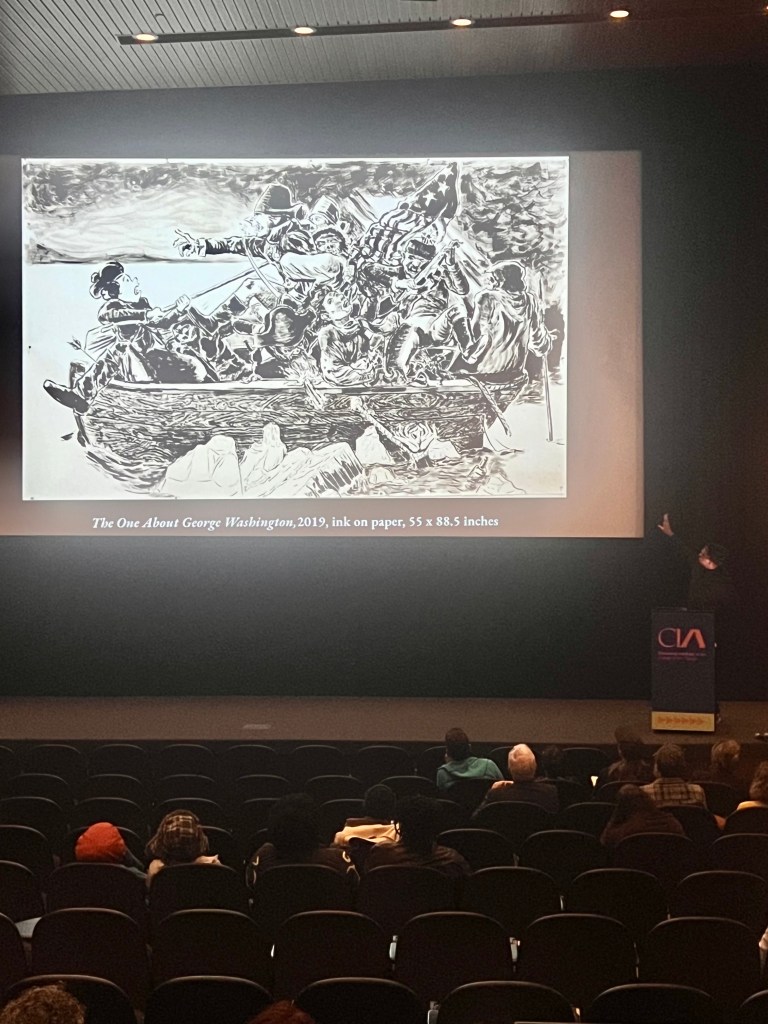

A fan of Spiegleman, Gibson found his description of comic and caricature to be a guiding force in his own work. In a previous talk, at the Barnes Foundation in Miami, he describes caricature as “a friend of his”, and now he sees it in everything, and furthermore, embraces it fully. His ability to illuminate layers on lateral levels of truth and trickery… purity and pejorative… is… a courageous approach, given that caricature can often be dismissed as cartoon-ish, playful and/or whimsical. There is no room to take anything at face value, particularly in art, and this lecture was a reminder that smiling faces… sometimes, they don’t tell the truth, and this can also be true of the canvas. Gibson believes that oftentimes we live with the dupe, the copy, the myth, the version that was handed down rather than the one that was real. Especially historically speaking, because years ago, artists were trying to catch up with documenting history in paintings and beyond. Using his favorite example, an Emmanuel Gottlieb Leutze painting titled Washington Crossing the Delaware, he challenged the thought of the image becoming the narrative for art gazers without realizing that what we see in museums, may not be the original or even a true depiction of the event portrayed. From here he showed us the actual original piece that had been destroyed, and it told a different story. He explored it even further in his piece, The One About George Washington, carrying on the concept through his caricatured version.

Duplication and distortion shape history, and his examination of the way history is told, who tells it, and how it gets reshaped over time is something I hold on to from his presentation. The power of imagery is indeed shaping me, but seeing the satire explained made for an interesting evening.

Gibson also reflected on his own journey as an artist, tracing it back to September 11, 2001, which coincided with the beginning of his MFA journey at Yale. That moment led to a seven-year hiatus, a time of pause and reflection that eventually brought him to Philadelphia, where he sought to be closer to history. He spoke about historical figures he critiques in his work, tying them to the broader themes of hoarding as death and how the accumulation of land, power, and resources leads to destruction rather than progress. He reminded the audience that history isn’t just about the marginalized—it implicates everyone, shaping a shared reality, whether we acknowledge it or not, specifically noting that white people lived through segregation too.

Gibson described the artist’s journey as a form of processing—His Town Crier series embodies this. The 4-8 hour bursts of creations are a response to the world and the overwhelming news cycles thereof. It essentially became his visual way of thinking and processing the influx of disheartened and other difficult emotional weight that was becoming commonplace. Satire is shown, but so is reality and he does not want us to forget! He challenged the audience to reflect on the things that we will forget about today in the future.

His painting process—which involves ink on canvas—is a mix of collage, historical reference, and contemporary critique. This philosophy is present throughout his work. Biden’s Entry into Washington, Klansman (2021), and Boys Will Be Boys reflect not only on historical anxieties but also the physicality of power—who enacts it, who cleans up after it, and how it manifests in different eras. Gibson’s work consistently captures the angst of the present moment, but he also speaks to hope and resistance, insinuating that certain failures can be our rewards. One of the most thought-provoking aspects of the lecture was his discussion on time, how our perception of history and time shifts, and how atemporality (“ity” of being unaffected by time or timeless) influences the way we engage with the past, present, and future. He further questions if our concept of the shift is in fact, shifting. In a single space, people tend to exist within their own time, their own desires, their own moment of presence. In many ways, this echoes the way art functions—it exists in a moment, yet it is something we can always return to. His work doesn’t sacrifice subject matter but materializes his maturing mastery of monumenting memory. In my opinion, Gibson’s art is a conversation. It has both narrative intensity and argumentative tenacity. I often wonder what any artist’s real objective is for their creative outlets, and appreciate it when there is an invitation to think and rethink about the work. The intricacies of Gibson’s work is not art at a glance. It can’t just be looked at once, I guarantee you’ll miss a reference, the irony or the subtle (or obvious) satire. But if you look again, you might find something new in it, and I find that quite beautiful.

As the lecture wrapped up, Gibson left us with some frames for reflection— not just for artists, but for anyone navigating creativity, history, and personal growth.

He posed three important questions:

- Does it have to be said?

- Does it have to be said by me?

- Does it have to be said right now?

These questions challenged us to consider our role in the conversations we engage in—when to speak, when to listen, and when to let things unfold. Most importantly, Gibson emphasized the necessity of caring for oneself as an artist—structuring life in a way that allows for creative sustainability and personal well-being. This presentation was a reminder that art is not just about representation—it’s about responsibility, reflection, and reckoning with the stories we choose to tell.

And that is something to return to—time after time.

Anyways, CIA has posted the video of the lecture if you want to check it out:

https://www.cia.edu/events/mark-thomas-gibson-time-after-time/